What's your anti-drug? Well, it might well be hemopressin. At least, that's probably your anti-marijuana.

What's your anti-drug? Well, it might well be hemopressin. At least, that's probably your anti-marijuana.

Hemopressin is a small protein that was discovered in the brains of rodents in 2003: its name comes from the fact that it's a breakdown product of hemoglobin and that it can lower blood pressure.

No-one seems to have looked to see whether hemopressin is found in humans, yet, but it seems very likely. Almost everything that's in your brain is in a mouse's brain, and vice versa.

Pharmacologically, hemopressin's literally an anti-marijuana molecule: it's an inverse agonist at CB1 receptors, which are the ones targeted by the psychoactive compounds in marijuana, and also by the neurotransmitters known as endocannabinoids. Cannabinoids turn CB1 receptors on, hemopressin turns them off.

Artificial CB1 blockers were developed as weight loss drugs, and one of them, rimonabant, made it onto the market - but it was banned after it turned out that it caused depression and anxiety in many people.

So hemopressin is Nature's rimonabant: in which case, it ought to do what rimonabant does, which is to reduce appetite. And indeed a Journal of Neuroscience paper just out from Godd et al shows that it does just that, in rats and mice: injections of hemopressin reduced feeding.

Interestingly, this worked even when it was injected by the standard route under the skin - many proteins can't enter the brain if they're given this way, because they can't cross the blood-brain barrier, meaning that they have to be injected directly into the brain, which makes researching them much harder. So hemopressin, with any luck, will be pretty easy to study. Any volunteers for the first human trial...?![]() Dodd, G., Mancini, G., Lutz, B., & Luckman, S. (2010). The Peptide Hemopressin Acts through CB1 Cannabinoid Receptors to Reduce Food Intake in Rats and Mice Journal of Neuroscience, 30 (21), 7369-7376 DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5455-09.2010

Dodd, G., Mancini, G., Lutz, B., & Luckman, S. (2010). The Peptide Hemopressin Acts through CB1 Cannabinoid Receptors to Reduce Food Intake in Rats and Mice Journal of Neuroscience, 30 (21), 7369-7376 DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5455-09.2010

This Is Your Brain's Anti-Drug

08.10

08.10

wsn

wsn

The Decline and Fall of the Cannabinoid Antagonists

04.35

04.35

wsn

wsn

Cannabinoid Receptor, Type 1 (CB1) antagonists were supposed to be the next big thing.

It all started off well. Rimonabant, manufactured by Sanofi, was the first CB1 antagonist to become available for human use: it hit the European market in 2006, as Acomplia. Four large clinical trials showed convincingly that it helped people lose weight. Rival drug companies were hard at work developing other CB1 antagonists, and inverse agonists (similar, but even more potent). The "bants" included Merck's taranabant, Pfizer's otenabant, and more.

Even more excitingly, there were indications that CB1 antagonists could do more than help people lose weight: they might also be useful in helping people quit smoking, alcohol or drugs. The animal evidence that CB1 antagonists did this was strong. Human trials were underway. Optimists saw rimonabant and related drugs as offering something unprecedented: self-control in a pill, abstinence on demand.

But it ended in tears, literally. Rimonabant was pulled from the European market in late 2008; it was never approved in the USA at all. After rimonabant was withdrawn, drug companies abandoned the development of other CB1 antagonists.

The problem was that they made people depressed. In several large clinical trials of rimonabant it raised the risk of suffering depression and other psychiatric problems, like anxiety and irritability, compared to placebo. The reported rates of these symptoms ranged from a few % up to over 40% depending upon the population, but there have been no trials (except very small ones) in which these effects weren't seen. This means that CB1 antagonists cause depression rather more consistently than antidepressants treat it.

Merck have just released the data from a trial of taranabant: A clinical trial assessing the safety and efficacy of taranabant, a CB1R inverse agonist, in obese and overweight patients. It makes a fitting epitaph to the CB1 antagonists. They gave taranabant, at a range of doses, or placebo, to overweight people to go alongside diet and exercise to help them lose weight. The results were extremely similar to those seen with rimonabant; the drug worked:

But there were side effects. Alongside things like nausea, vomiting, and sweating, about 35% of people taking high doses of taranabant reported "psychiatric disorders". 20% of people on placebo also did, so this is not quite as bad as it first appears, but it's still striking, especially since a number of people on high doses of taranabant reported suicidal thoughts or behaviours...

But there were side effects. Alongside things like nausea, vomiting, and sweating, about 35% of people taking high doses of taranabant reported "psychiatric disorders". 20% of people on placebo also did, so this is not quite as bad as it first appears, but it's still striking, especially since a number of people on high doses of taranabant reported suicidal thoughts or behaviours...

Suicidal ideation was reported in three patients in the taranabant 6-mg group in year 1 and in one patient in the 4-mg group in year 2. There was one suicide attempt reported in a patient with a previous history of suicide attempts in the 6/2-mg group while the patient was receiving 2-mg, and one episode of suicidal behavior reported in a patient in the 6/2-mg group while the patient was receiving 6-mg. There were no completed suicides. The adjudication of possibly suicide-related adverse experiences during years 1 and 2 indicated an increased incidence of suicidality in the taranabant groups...

Safety concerns have plagued weight loss medications for decades. The problem is not that they don't work: plenty of drugs cause weight loss, at least for as long as you keep taking them. But unfortunately, there's always a 'but'.

Fenfluramine worked, but it caused heart valve defects, and was banned. Sibutramine works, but it's just been suspended from the European market due to concerns over heart disease (a different kind). Amphetamine-like stimulants such as phentermine work, but they're addictive and liable to abuse. What with rimonabant and sibutramine are gone, the only weight-loss drug approved for use in Europe is orlistat, which seems to be safe, but has some very unpleasant side effects...

Still, CB1 antagonists have a unique mechanism of action: they block the CB1 receptor, which is what gets activated by the cannabinoid ingredients in marijuana, and also the brain's own cannabinoids neurotransmitters (endocannabinoids). The past five years has seen a huge amount of research showing that the CB1 receptor is involved in everything from memory and emotion to motivation, pain sensation and hormone secretion. We recently learned that there are even CB1 receptors on the tongue that regulate taste.

CB1 is able to do all this because it's found almost everywhere in the brain. To simplify, but only a little, the endocannabinoid system is a general feedback mechanism, which allows cells on the receiving end of neural transmission to "talk back" to the neuron sending them signals; if they're receiving lots of input, they tell the cell sending the signals to quiet down. In other words, endocannabinoids regulate the release of just about every other neurotransmitter. To be honest, given how important the system is in the brain, it's surprising that depression and anxiety are the biggest problems with CB1 antagonists.

For all that, we still don't know why they cause psychiatric symptoms, although a number of mechanisms have been suggested. Hopefully, someone will work this out sooner or later, since that would add an important piece to the puzzle of what goes on in the brain during depression...

Dope, Dope, Dopamine

14.10

14.10

wsn

wsn

When you smoke pot, you get stoned.

In Central nervous system effects of haloperidol on THC in healthy male volunteers, Liem-Moolenaar et al tested whether an antipsychotic drug would modify the psychoactive effects of Δ9-THC, the main active ingredient in marijuana. They took healthy male volunteers, who had moderate experience of smoking marijuana, and gave them inhaled THC. They were pretreated with 3 mg haloperidol, or placebo.

They found that haloperidol reduced the "psychosis-like" aspects of the marijuana intoxication. However, it didn't reverse the effects of THC of cognitive performance, the sedative effects, or the user's feelings of "being high".

This makes sense, if you agree with the theory that the psychosis-like effects of THC are related to dopamine. Like all antipsychotics, haloperidol blocks dopamine D2 receptors, and increased dopamine transmission has long been implicated in psychosis; some studies have found that THC causes increased dopamine release in humans (although others have not.)

Heavy marijuana use probably raises the risk of psychotic illnesses, like schizophrenia, although this is still a bit controversial, but it's accepted that some people do experience psychotic-type symptoms while stoned. So Liem-Moolenaar et al's conclusion that "psychotic-like effects induced by THC are mediated by dopaminergic systems" while the other aspects of being stoned are mediated by other brain systems, is not unreasonable, and this study is a nice example of the 'pharmacological dissection' of drug effects.

Still, like most papers of this kind, this leaves me wanting to know more about the subjective effects experienced by the volunteers. What did it feel like to get stoned on haloperidol? The paper tells us that

THC caused a significant increase of 2.5 points in positive PANSS, which was significantly reduced by 1.1 points after pre-treatment with haloperidol... Haloperidol completely reversed THC-induced increases in ‘delusions’ and ‘conceptual disorganization’ and almost halved the increase in ‘hallucinatory behaviour’. Although not statistically significant, haloperidol seemed to increase the items ‘conceptual disorganization’, ‘suspiciousness/persecution’ and ‘hostility’ compared with placebo.The PANSS being a scale used to rate someone's "psychotic symptoms". On the other hand haloperidol had no significant effect on the users' self-rated Visual Analogue Scales (VAS) scores for things like "altered external perception" and "feeling high".

But surely the haloperidol must have changed what it felt like in some way. It must have changed how people thought, felt, perceived, heard, and so forth. These kinds of rating scales are useful for doing statistics with, but they can no more capture the full depth of human experience than a score out of 5 stars substitutes for a full Roger Ebert movie review.

But surely the haloperidol must have changed what it felt like in some way. It must have changed how people thought, felt, perceived, heard, and so forth. These kinds of rating scales are useful for doing statistics with, but they can no more capture the full depth of human experience than a score out of 5 stars substitutes for a full Roger Ebert movie review.This matters, because it's not clear whether haloperidol really reduced "psychosis-like experiences", or whether it just sedated people to the extent that they were less likely to talk about them. In other words, its not clear whether the scores on the rating scales changed in "specific" or a "non-specific" way. This is no criticism of Liem-Moolenaar, though, because it's a general problem in psychopharmacology. For example, a sleeping pill could reduce your score on most depression rating scales, even if it had no effect on your mood, because insomnia is a symptom of depression.

There are various ways to try to work around these issues, but ultimately I suspect that there's no substitute for personal experience, with direct observation of other people taking the drugs coming second, and rating scales a distant third. Of course, direct observation is unsystematic, and prone to bias, and few would say it was practical for psychopharmacologists to go around drugging themselves and each other... but life is more than a series of numbers.

Link: On Being Stoned (1971) by Charles Tart is a classic book which used a very detailed questionnaire to investigate what it's like to be stoned, although the methodology was hardly rigorous.

Posted in

books,

CNR1,

drugs,

marijuana,

mental health,

papers,

schizophrenia

Posted in

books,

CNR1,

drugs,

marijuana,

mental health,

papers,

schizophrenia

The Sweet Taste of Cannabinoids

07.44

07.44

wsn

wsn

Every stoner knows about the munchies, the fondness for junk food that comes with smoking marijuana. Movies have been made about it.

Every stoner knows about the munchies, the fondness for junk food that comes with smoking marijuana. Movies have been made about it.

It's not just that being on drugs makes you like eating: stimulants, like cocaine and amphetamine, decrease appetite. The munchies are something specific to marijuana. But why?

New research from a Japanese team reveals that marijuana directly affects the cells in the taste buds which detect sweet flavours - Endocannabinoids selectively enhance sweet taste.

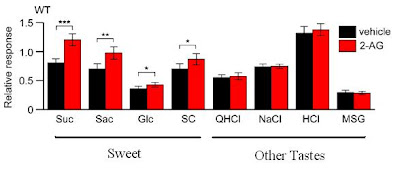

Yoshida et al studied mice, and recorded the electrical signals from the chorda tympani (CT), which carries taste information from the tongue to the brain.

They found that injecting the mice with two chemicals, 2AG and AEA, markedly increased the strength of the signals produced in response to sweet tastes - such as sugar, or the sweetener saccharine. However, neither had any effect on the strength of the response to other flavours, like salty, bitter, or sour. Mice given endocannabinoids were also more eager to eat and drink sweet things, which confirms previous findings.

2-AG and AEA are both endocannabinoids, an important class of neurotransmitters. Marijuana's main active ingredient, Δ9-THC, works by mimicking the action of endocannabinoids. Although Δ9-THC wasn't tested in this study, it's extremely likely that it has the same effects as 2-AG and AEA.

This is an important finding, because CB1 receptors are already known to regulate the pleasurable response to sweet foods (amongst other things) in the brain. These new data don't challenge this, but suggest that CB1 also modulates the most basic aspects of sweet taste perception. The munchies are probably caused by Δ9-THC acting at multiple levels of nervous system.

This paper also sheds light on CB1 antagonists. Given that drugs which activate CB1 make people eat more, it would make sense if CB1 blockers made people eat less, and therefore lose weight, a kind of anti-munchies effect. And indeed they do. Which is why rimonabant, a CB1 antagonist, was released onto the market in 2006 as a weight loss drug. It worked pretty well, although unfortunately it also it caused clinical depression in some people, so it was banned in Europe in 2008 and was never approved in the USA for the same reason.

The depression was almost certainly caused by antagonism at CB1 receptors in the brain, but Yoshida et al's findings suggest that a CB1 antagonist which didn't enter the brain, and only affected peripheral sites such as the taste buds, might be able to make people less fond of sweet foods without causing the same side-effects. Who knows - in a few years you might even be able to buy CB1 antagonist chewing gum to help you stick to your diet...![]() Yoshida, R., Ohkuri, T., Jyotaki, M., Yasuo, T., Horio, N., Yasumatsu, K., Sanematsu, K., Shigemura, N., Yamamoto, T., Margolskee, R., & Ninomiya, Y. (2009). Endocannabinoids selectively enhance sweet taste Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107 (2), 935-939 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0912048107

Yoshida, R., Ohkuri, T., Jyotaki, M., Yasuo, T., Horio, N., Yasumatsu, K., Sanematsu, K., Shigemura, N., Yamamoto, T., Margolskee, R., & Ninomiya, Y. (2009). Endocannabinoids selectively enhance sweet taste Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107 (2), 935-939 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0912048107

More on Medical Marijuana

08.07

08.07

wsn

wsn

Previously I wrote about a small study finding that smoked marijuana helps with HIV-related pain. In the last month, two more clinical trials of medical marijuana - or rather, marijuana-based drugs - for pain have come out.

Previously I wrote about a small study finding that smoked marijuana helps with HIV-related pain. In the last month, two more clinical trials of medical marijuana - or rather, marijuana-based drugs - for pain have come out.

First, the good news. Johnson et al tested a mouth spray containing the two major psychoactive chemicals in marijuana, THC and CBD. Their patients were all suffering from terminal cancer, which believe it or not, is quite painful. Almost all of the subjects were already taking high doses of strong opiate painkillers: a mean of 270 mg morphine or equivalent each day, which is enough to kill someone without a tolerance. (A couple of them were on an eye-watering 6 grams daily). Yet they were still in pain.

Patients were allowed to use the cannabinoid spray as often as they wanted for 2 weeks. Lo and behold, the THC/CBD spray was more effective than an inactive placebo spray at relieving pain. The effect was modest, but statistically significant, and given what these people were going through I'm sure they were glad of even "modest" effects. A third group got a spray containing only THC, and this was less effective than the combined THC/CBD - on most measures, it was no better than placebo. THC is often thought of as the single "active ingredient" in marijuana, but this suggests that there's more to it than that. This was a relatively large study - 177 patients in total - so the results are pretty convincing, although you should know that it was funded and sponsored by GW Pharma, whose "vision is to the global leader in prescription cannabinoid medicines". Hmm.

Overall, this is further evidence that marijuana-based drugs can treat some kinds of pain, although maybe not all of them. I have to say, though, that I'm not sure that we needed a placebo-controlled trial to tell us that terminal cancer patients can benefit from medical marijuana. If someone's dying from cancer, I say let them use whatever the hell they want, if they find it helps them. Dying patients used to be given something called a Brompton cocktail, a mixture of drugs that would make Keith Richards jealous: heroin, cocaine, marijuana, chloroform, and gin, in the most popular variant.

And why not? There were no placebo-controlled trials proving that it worked, but it seemed to help, and even if it was just a placebo (which seems unlikely), placebo pain relief is still pain relief. I'm not saying that these kinds of trials aren't valuable, but I don't think we should demand cast-iron proof that medical marijuana works before making it available to people who are suffering. People are suffering now, and trials take time.

Johnson JR, Burnell-Nugent M, Lossignol D, Ganae-Motan ED, Potts R, & Fallon MT (2009). Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Study of the Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of THC:CBD Extract and THC Extract in Patients With Intractable Cancer-Related Pain. Journal of pain and symptom management PMID: 19896326

Selvarajah D, Gandhi R, Emery CJ, & Tesfaye S (2009). A Randomised Placebo Controlled Double Blind Clinical Trial of Cannabis Based Medicinal Product (Sativex) in Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: Depression is a Major Confounding Factor. Diabetes care PMID: 19808912

The Politics of Psychopharmacology

15.59

15.59

wsn

wsn

It's always nice when a local boy makes good in the big wide world. Many British neuroscientists and psychiatrists have been feeling rather proud this week following the enormous amount of attention given to Professor David Nutt, formerly the British government's chief adviser on illegal drugs.

It's always nice when a local boy makes good in the big wide world. Many British neuroscientists and psychiatrists have been feeling rather proud this week following the enormous amount of attention given to Professor David Nutt, formerly the British government's chief adviser on illegal drugs.

Formerly being the key word. Nutt was sacked (...write your own "nutsack" pun if you must) last Friday, prompting a remarkable amount of condemnation. Critics included the rest of his former organisation, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), and the Government's Science Minister. The UK's Chief Scientist also spoke in favour of Nutt's views. Journalists joined in the fun with headlines like "politicians are intoxicated by cowardice".

"The sacking of a government adviser on drugs shows Britain's politicians can't cope with intelligent debate... the position of the Labour government and of the leading opposition party, the Conservatives, which vigorously supported Nutt's sacking, has no merit at all. It deals a significant blow both to the chances of an informed and reasoned debate over illegal drugs, and to the parties' own scientific credibility."They also have an interview with the man himself.

What happened? The short answer is a lecture Nutt gave on the 10th October, Estimating Drug Harms: A Risky Business? I'd recommend reading it (it's free). The Government's dismissal e-mail gave two reasons why he had to go - firstly, "Your recent comments have gone beyond [matters of evidence] and have been lobbying for a change of government policy" and secondly, "It is important that the government's messages on drugs are clear and as an advisor you do nothing to undermine public understanding of them."

Many people believe that Nutt was fired because he argued for the liberalization of drug laws, or because he claimed that the harms of some illegal drugs, such as cannabis, are less severe than those of legal substances like tobacco and alcohol. On this view, the government's actions were "shooting the messenger", or dismissing an expert because they didn't like to hear to the facts. It seems to me, however, that the truth is a little more nuanced, and even more stupid.

Nutt's lecture, if you read the whole thing as opposed to the quotes in the media, is remarkably mild. For instance, at no point does he suggest that any drug which is currently illegal should be made legal. The changes he "lobbies for" are ones that the ACMD have already recommended, and this lobbying consists of nothing more than tentative criticism of the stated reasons for the rejection of the ACMD's advice. The ACMD is government's official expert body on illicit drugs, remember.

The issue Nutt focusses on is the question of whether cannabis should be a "Class C" or a "Class B" illegal drug, B being "worse", and carrying stricter penalties. It was Class B until 2004, when it was made Class C. In 2007, the Government asked the ACMD to advise on whether it should be re-reclassified back up to Class B. This was in response to concerns about the impact of cannabis on mental health, specifically the possibility that it raises the risk of psychotic illnesses.

The resulting ACMD report is available on the Government's website. They concluded that while cannabis use is certainly not harmless, "the harms caused by cannabis are not considered to be as serious as drugs in class B and therefore it should remain a class C drug."

Despite this, the Government took the decision to reclassify cannabis as Class B. In his lecture Nutt criticizes this decision - slightly. Nutt quotes the Home Secretary as saying, in response to the ACMD's report -

"Where there is a clear and serious problem [i.e. cannabis health problems], but doubt about the potential harm that will be caused, we must err on the side of caution and protect the public. I make no apology for that. I am not prepared to wait and see."Nutt describes this reasoning as -

"the precautionary principle - if you’re not sure about a drug harm, rank it high... at first sight it might seem the obvious decision – why wouldn’t you take the precautionary principle? We know that drugs are harmful and that you can never evaluate a drug over the lifetime of a whole population, so we can never know whether, at some point in the future, a drug might lead to or cause more harm than it did early in its use."But he says, there's more to it than this. Firstly, we don't know anything about how classification affects drug use. The whole idea of upgrading cannabis to Class B to protect the public relies on the assumption that it will reduce drug use by deterring people from using it. But there is no empirical evidence as to whether this actually happens. As Nutt points out, stricter classification might equally well increase use by making it seem forbidden, and hence, cooler. (If you think that's implausible, you have forgotten what it is like to be 16.) We just don't know.

Second, he says, the precautionary principle devalues the evidence and is thereby self-defeating because it means that people will not take any warnings about drug harms seriously - "[it] leads to a position where people really don’t know what the evidence is. They see the classification, they hear about evidence and they get mixed messages. There’s quite a lot of anecdotal evidence that public confidence in the scientific probity of government has been undermined in this kind of way." Can anyone really dispute this?

Finally, he raises the MMR vaccine scare as an example of the precautionary principle ironically leading to concrete harms. Concerns were raised about the safety of a vaccine, on the basis of dubious science. As a result, vaccine coverage fell, and the incidence of measles, mumps and rubella in Britain rose for the first time in decades. The vaccine harmed no-one; these diseases do. We just don't know whether cannabis reclassification will have similar unintended consequences.

That's what the Home Secretary described as "lobbying for a change of government policy". I wish all lobbyists were this reasonable.

The Home Secretary's second charge against Nutt - "It is important that the government's messages on drugs are clear..." - is even more specious. Nutt's messages were the ACMD's messages, and as he points out, the only lack of clarity comes from the fact that the government and their own Advisory Council disagree with each other. This is hardly the ACMD's fault, and it's certainly not Nutt's fault for pointing it out.

All of this is doubly ridiculous because of one easily-forgotten fact - cannabis was downgraded from Class B to Class C in 2004 by the present Labour Party government. Nutt's "lobbying" therefore consists of a recommendation that the government do something they themselves previously did. And if the government are worried about the clarity of their message, the fact that they themselves were saying that cannabis was benign enough to be a Class C drug just 5 years ago might be somewhat relevant.

The manuscript falls short of its goals in several respects: The basic phenomenon ... is barely presented... The style and language of the review leave a lot to be desired... The citations and reference list are appalling.The same reviewer also criticized the basic argument of my article, implicitly branding the whole paper - all 10,000 words of it, which took dozens of hours to write - a complete waste of time.

Ouch. But as an academic, giving, and receiving, this kind of treatment is all part of the job, and that's just as it should be. I'm confident that my argument is sound, so I'm going to take the criticisms on board, rewrite the paper appropriately, and submit it to another journal. What I'm not going to do is bear a grudge against the reviewer. (Well maybe a little: the references weren't that bad.) To be fair, unlike Nutt's, this review was not made in the public domain, but then, I'm not a Government elected by the public.

Nutt's mistake was to think that it's possible to have a serious debate about a serious political issue. In fact, it was probably not such a bad mistake, since the job of the ACMD, as the Government sees it, is a fairly pointless one: their job is to give expert advice and then let it be ignored. As various ACMD members have noted, they work for free, in the public interest. If I were on the Committee, I would resign now, not just out of sympathy for Nutt, but because it's a crap job.

In his dismissal letter, the Home Secretary told Nutt, "It is not the job of the Chair of the Government's advisory Council to initiate a public debate on the policy framework for drugs". I would have thought he was exactly the person who should do this if such a debate was necessary, as it obviously is. Well, now we know better. It wasn't his job. Although, thanks to the government who sacked him, a drug debate is now going on in the British media for the first time in years. In the long run, Nutt's most important action as Chair of the ACMD may well have been getting sacked from it.

[BPSDB]

Daniel Cressey (2009). Sacked science adviser speaks out Nature